“Let the cold world do its worst; one thing I know — there’s a grave somewhere for me. The world may go on just as it’s always done, and take everything from me — loved ones, property, everything — but it can’t take that. Some day I’ll lie down in it and forget it all, and my poor broken heart will be at rest.”

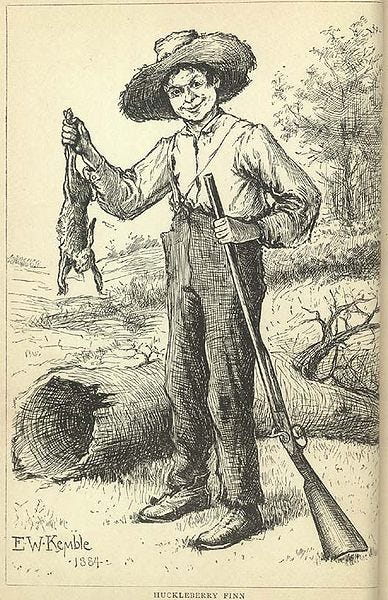

So says the self-proclaimed ‘Duke of Bridgewater’ as he introduces himself to Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn the direct sequel of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The work is among the first in American literature to be written throughout in vernacular English, characterized by local color regionalism. The book is set in a Southern antebellum society and is known to be a scathing satire on entrenched attitudes, particularly racism, as well as for its colorful descriptions of people and places along the Mississippi River.

As the Duke tells a sad tale of his hopeless circumstances, with him is his companion who shares a similar pitiful tale, even going so far as to one-up him. His companion is an older man in his 70s who claims to be the self-styled ‘dauphin, Louis XVII,’ going on to say:

“Yes, gentlemen, you see before you, in blue jeans and misery, the wanderin’, exiled, trampled-on and sufferin’ rightful King of France.”

Keep reading for a deep dive into the infamous conmen, the Duke and King in Mark Twain’s great American novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Sorry to disappoint you, but these aren’t a real Duke and King. No, they’re grifters out to con the people of more than one riverside town.

The conmen enter the narrative as inconvenient and troublesome as their reputation will soon reveal. After a few peaceful days on the raft, Huck is searching for some berries in a creek when he comes upon two desperate men. The men are obviously being chased, and Huck tells them how to lose the dogs, helping them to escape. The men, one around 70 and the other around 30 years old, join Huck and Jim on the raft.

Together, the duke and king portray themselves as down-and-out victims in order to curry favor through pity and to conceal their fraudulent intentions. Despite their efforts, Huck believes the men are simple conmen but decides not to challenge them in order to keep the peace.

At first, when the duke and the king first meet, they try to con each other. But they soon strike a truce and go off to con the whole world — or, at least what’s known of it along the Mississippi.

“Like as not we got to be together a blamed long time on this h-yer raft, Bilgewater, and so what’s the use o’ your bein’ sour? It’ll only make things on-comfortable. It ain’t my fault I warn’t born a duke, it ain’t your fault you warn’t born a king — so what’s the use to worry? Make the best o’ things the way you find ’em, says I — that’s my motto. This ain’t no bad thing that we’ve struck here — plenty grub and an easy life — come, give us your hand, duke, and le’s all be friends.”

Talk about meet-cute.

Our first impressions of this duo give us the sense that the Duke holds the higher moral ground of the pair, which really isn’t saying much. Next, we learn that it’s not over friendship or loyalty for one another that they pair up, but rather for “plenty grub and an easy life.” In other words, we wouldn’t bet on this team in Dancing with the Stars.

Okay, but other than serving as examples of What-Not-To-Do, the Duke and King have two significant roles in the novel. First is they’re essentially the bizarro-world version of Huck and Jim, and secondly, they play a major part in Huck’s maturation.

From here, the schemes of the conmen direct the plot. As the duke and king become permanent passengers on Jim and Huck’s raft, committing a series of confidence schemes upon unsuspecting locals. The duke even goes so far as to dress Jim up as an “Arab” to draw less attention and so he can move along the raft without bindings.

They stop in the one-horse town of Pokeville, which is practically deserted because of a nearby camp meeting. When the duke heads off in search of the printing shop, the king decides to attend the meeting. At the meeting, the people sing hymns and go up to the pulpit for forgiveness. It is here where the king professes to be an old pirate who has reformed and seen the error of his ways. Add in some crocodile tears and he’s able to walk away with $87 and a bottle of whiskey. Not too shabby.

The inclusion of the camp meeting is a perfect example of the confidence man. Along with its playful burlesque of religion, the camp meeting shows a gullible audience that is swindled because of its faith. The ensuing scene is reminiscent of George Washington Harris’s “Sut Lovingood’s Lizards” and Johnson J. Hooper’s “Simon Suggs Attends a Camp Meeting.” Both authors were influential for Twain and reflect a society that is scammed because of its misplaced faith or hypocrisy.

“First they done a lecture on temperance; but they didn’t make enough for them both to get drunk on. Then in another village they started a dancing school; but they didn’t know no more how to dance than a kangaroo does; so the first prance they made, the general public jumped in and pranced them out of town. Another time they tried a go a yellocution; but they didn’t yellocute long till the audience got up and give them a solid cussing and made them skip out.”

If the antics of the duke and king weren’t crazy enough, the duke teaches the king Shakespeare which results in their next con — planning a three-night performance called ‘The Royal Nonesuch.’ However, the play turns out to be only a couple of minutes’ worth of an absurd, bawdy sham where a painted, naked king spews nonsense.

By the third night of ‘The Royal Nonesuch’, the townspeople prepare for their revenge. But before they can dish it out the two cleverly skip town together with Huck and Jim just before their performance is to begin.

In the next town, the two swindlers then impersonate the brothers of Peter Wilks, a recently deceased man of property. Mary Jane, Joanna, and Susan Wilks are the three young nieces of their wealthy-deceased guardian. The Duke and the King try to steal their inheritance by posing as Peter’s estranged brothers from England. To match accounts of Wilks’s brothers, the king attempts an English accent and the duke pretends to be a deaf-mute while starting to collect Wilks’s inheritance.

Huck decides that Wilks’s three orphaned nieces, who treat Huck with kindness, do not deserve to be cheated thus and so he tries to retrieve for them the stolen inheritance. In a desperate moment, Huck is forced to hide the money in Wilks’s coffin, which is abruptly buried the next morning.

After the failed attempt to defraud the Wilks nieces, Huck describes the subsequent series of attempted cons by the duke and the king. The tone of the passage is humorous since it shows that the conmen are as inept as they are persistent. But Huck’s words also express a sense of exhaustion and frustration. At this point in the book, he desperately wishes to get away from these increasingly dangerous men.

When the funeral takes place, things become even more complicated when not only is the gold mysteriously found inside the coffin but the real brothers of the dead man show up and get into an argument with the king and the Duke. Huck attempts to get back to the raft and leave without them, but the two villains manage to escape by the skin of their teeth and catch a ride again with Huck and Jim.

At the next town they stop at, the two men inexplicably sell Jim away to some farmers (who later conveniently turn out to be Tom Sawyer’s aunt and uncle), as revenge for Huck ruining their previous scheme.

The King sets Jim up to be captured and uses the $40 reward to get drunk. When pressed, the duke lies to Huck about Jim’s whereabouts, although, to his credit, he almost tells Huck the truth. Making him a little better than the King. At least he’s not a complete sociopath like his older counterpart.

It is not until later when Jim tells the family about the two grifters and the new plan for ‘The Royal Nonesuch’ that the townspeople capture the duke and king, who are deservingly tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail.

The Duke and King serve as an important reminder of what Huck and Jim could become without their morals. At first, Huck is having a grand old time. No rules, no sitting up straight, and definitely no Sunday School. Soon enough, he starts to wonder if maybe life on the lam isn’t so great after all, especially when the king and duke start trying to cheat the Wilk nieces out of their inheritance.

And when the duke and king end up tarred and feathered, Huck realizes that he’s probably better off staying on the right side of the law. And that’s a lesson worthy of royalty. The two are selfish, greedy, deceptive, and debauched, but sometimes their actions expose and exploit societal hypocrisy in a way that is somewhat attractive and also rather revealing. Though the exploits of the duke and king can be farcical and fun to watch, the two demonstrate an absolute, hideous lack of respect for human life and dignity.

At first, the men appear harmless, and Huck quietly rejects their preposterous claims of royalty. His recognition of their true character is important, for he understands that the two pose a particular threat to Jim.

Huck’s insight, however, is not surprising, for the men are simply exaggerations of the characters that Huck and Jim have already encountered during their journey. Huck has learned that society is not to be trusted, and the duke and the king quickly show that his concern is legitimate.

If you haven’t already, make sure to get a copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It’s a book that’s worth multiple readings.